Summary

Our preprint asks whether you can spot tomorrow’s “up-and-coming” lineages by reading patterns already encoded in today’s phylogenetic tree. We introduce a simple statistic– coalescent odds— that scores each lineage’s tendency to spawn descendants. It’s fast, interpretable, and designed for messy real-world surveillance. Here’s the preprint. And, here’s the R package.

Why this matters

Epidemiologists sift through pathogen genomes to catch variants early. But turning millions of sequences into an early-warning signal is hard. We asked a basic question: does the shape of the tree itself contain enough signal to flag which lineages are likely to grow?

This isn’t a new problem, and ours isn’t the first proposed solution. For example, the local branching index (LBI) is also a simple statistic which can be readily calculated from a tree, and which is the default statistic reported on nextstrain as a proxy for pathogen fitness, e.g. here. There’s also a lot of related work to pickout “clusters” or cryptic population structure in phylogenies, and these can be used as the basis for epidemic early warning signals.

But we had another look at this problem to see if we can come with a method that checks some boxes:

- Can we define a statistic that is readily interpretable and based on a classic population-genetic model?

- Can we make it work with messy real-world data that is rife with sampling bias?

- Can we make it scalable to very large real-world datasets?

- Can we fit the model to data w/o relying on arbitrary hyperparameters (e.g. clustering thresholds)?

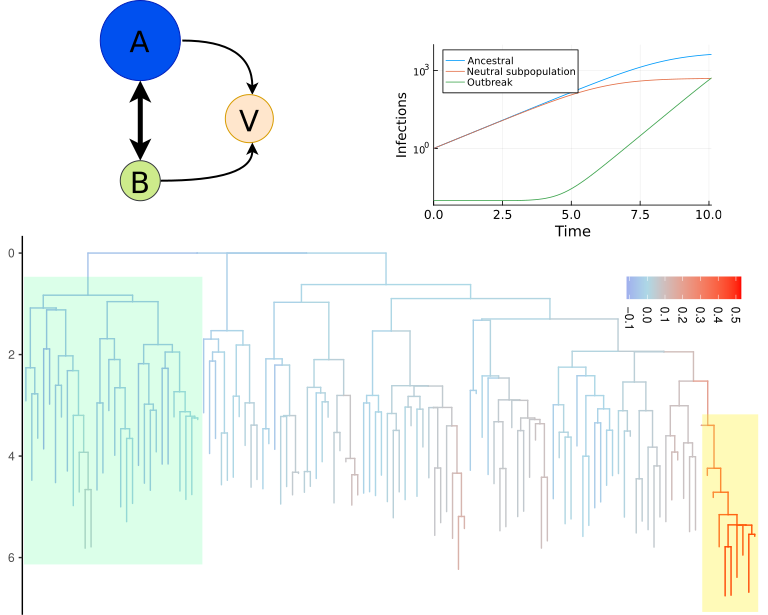

The core idea: coalescent odds

Funnily enough, one of the most useful ways to study phylogenies is to read them ‘backwards’ in time.

Branches coalesce when two lineages share a recent ancestor. If a lineage tends to sit near lots of recent coalescent events, it may be on a growth trajectory. Or it may just be in a region that is highly sampled! It’s important to have a method that can distinguish between these mechanisms.

We define a continuous, heritable “propensity to coalesce” for each lineage. Intuitively, it’s a score for “how likely this lineage is to be the parent of many near-future samples.” From this, we compute coalescent odds (cod’s)-a per-lineage number that can be tracked over time.

In principle, this gives us a model-light approach, without heavy assumptions about evolution or fitness. Coalescent odds can vary in a flexible way across a phylogenetic tree, and we fit the model in a way that maximises the predictive power of the statistic for future growth.

While the basic model is not terribly scalable (certainly not in comparison to methods that use message-passing algorithms), we developed a number of very efficient and accurate approximations that make this applicable to trees with 000’s of samples.

What we found (in brief)

- Prediction. Given a tree built from genomes available today, can cod’s help identify lineages that will be more common tomorrow?

- Yes! Even with realistic noise, cod’s contain predictive information about short-term lineage growth- enough to improve triage over naive baselines.

- Temporal stability. The signal isn’t a one-off artifact when natural selection is at play; it persists across time when updated with new data.

- Robustness. Does it still work when sampling is uneven, noisy, or biased (as in real surveillance)?

- Because cod’s are model-light, it degrades gracefully under imperfect sampling. If informative metadata are available, sampling bias can be handled explicitly.

What’s next

One of the most exciting things about this approach is that there are many ways to build on it. Here’s what we’re working on now:

- Since we have essentially transformed estimating lineage fitness into a linear regression problem (read the preprint to see how), it is possible to include covariate data for each lineage. For example, imagine using deep learning or protein language models to independently estimate fitness; or deep mutational scanning; then these scores could be included when estimating cod’s to achieve an estimate of fitness that is using all the data- epidemiological, virological, and computational – to generate a combined estimate of fitness.

- One limitation of this approach is that it depends on the ability to estimate high-quality time-scaled phylogenies. This isn’t always possible; sometimes we deal with short and incomplete genomic data, and the best we can do is identify clusters. The good news is that the basic underlying model for cod’s could be used in this case as well. Showing how to do this will be very useful for applying these methods to new metagenomics surveillance systems.